In the age of sail names such as Mary Lacy, Hannah Snell, or woman known as William Brown and many more were connected to cases of women disguising themselves as men and signing up as seamen to serve in the Royal or Merchant Navy.

These women strove to escape their restrictive female bonds in an age where women were considered weak, not able to look after themselves without needing the protection and guidance of men. Why did they run away to sea? One good reason was to gain financial independence and freedom. The harsh life they signed up for had the compensation that any money they earned was theirs to spend as they liked. For those who chose this unconventional path the rewards of freedom from the narrow obedient life of a woman at home must have outweighed the difficulties and possibility of discovery. Others wished to become men, they preferred wearing male clothes and the company of men. Some must have sought excitement and adventure and some followed a man whom they were in love with.

The women, if discovered, were never punished but simply dismissed from the navy. Under the Admiralty rule, no women were allowed on board a naval vessel without the permission of the Admiralty, this would have most definitely included any female in the disguise of a man no matter how good a seaman they were. Some must have been discovered fairly quickly but many were only found out when they were about to be flogged and they voluntarily revealed their true identity or admitted it when they were in trouble. We don't know how many had a successful career without discovery except for a few cases after fighting in battles and being paid off they received a pension and ended their silence to tell their story. Mary Lacy was one of those women who fortunately decided to tell her fantastic story giving us a detailed picture of life as a sailor aboard a warship. In 1759 she went to sea in men's clothes as William Cavendish apprentice carpenter, the ship she joined was involved in the Seven Years War between Britain and France. In 1763 she decided to become a shipwright's apprentice based Portsmouth Dockyard and gained her certificate in 1770 despite being discovered and confessing she was a woman to two male colleagues who surprisingly swore to keep her secret.

However, rheumatoid arthritis meant she was no longer able to work in such a physically demanding environment and in order to gain a pension she revealed her identity as Mary Lacy and not William Chandler, as she later called herself. Her petition was successful and she retired publishing her story under the title The History of the Female Shipwright.

To successfully pass as a man in an extremely harsh and physical world these women learnt to fit in with the men, chewing tobacco, drinking and sometimes chasing women. Mary Lacy had proved by gaining her shipwright certificate to be a talented craftsman as well as a good imitator. In the case of a woman known as William Brown, whose real name is unknown, her seaman's skills enabled her to became the captain of the foretop. Her skill with sails and directing the crew in her section earned her the responsibility of an area that in storms and gales was very perilous; many were blown over board whilst at the top of the mast.

These stories and others show us that women found many guises in order to go to sea but often the most popular was as a ship's boy. The uniform of loose baggy clothes and hair worn long enabled women to pass themselves off as young boys, if discovery ended their journey or adventure; mention of it made short reading in the newspapers. For the stories which passed into song and legend you have to turn to the more dangerous women who went to sea as men and as pirates.

Sailors in Disguise

Women found many guises in order to go to sea but often the most popular was as a seaman!

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Monday, March 19, 2012

"William Brown"

|

| HMS Queen Charlotte bearing the flag of Vice Admiral Keith, Anchored in Cadiz Bay |

“Amongst the crew of the Queen Charlotte, 110 guns, recently paid off, is now discovered, was a female African, who served as a seaman in the Royal Navy for upwards of eleven years, several of which she has been rated able on the books of the above ship by the name of William Brown, and has served for some time as the captain of the fore-top, highly to the satisfaction of the officers. She is a smart well formed-figure, about five feet four inches in height, possessed of considerable strength and great activity; her features are rather handsome for a black, and she appears to be about 26 years of age. Her share of prize money is said to be considerable, respecting which she has been several times within the last few days at Somerset-place. In her manner she exhibits all the traits of a British tar, and takes her grog with her late mess-mates with the greatest gaiety. She says she is a married woman; and went to sea in consequence of a quarrel with her husband, who, it is said, has entered a caveat against her receiving her prize money. She declares her intention of again entering the service as a volunteer."

This is not borne out by the Queen Charlotte's muster lists. When the crew were paid off in August 1815, the only William Brown on the list was a 32 year old Scot who had transferred from the Cumberland a month earlier. The list does show though that a 21-year old William Brown had joined the crew from Grenada on May 23, 1815 as a 'landsman' (the least experienced rating), and was discharged a month later for 'being a female'. There is no record of any William Brown being appointed Captain of the fore-top for the Queen Charlotte.

However, this still makes Brown the first known black, biologically female individual to serve in the Royal Navy.

"Tom Bowling"

Served as a bosun's mate on various ships for over 20 years.

Elizabeth Bowden

Women At Sea: Witness for the Prosecution

Elizabeth Bowden (or Bowen) seems to have had it rough from the very beginning. Born into obscurity and poverty some time in 1793 in Truro, Cornwall, she seemed destined to a bleak life. Things went from bad to worse when she was orphaned at age twelve or thirteen.

Elizabeth had an older sister who, to the best of the girl's knowledge, lived in that haven of the Royal Navy: Plymouth. Being nothing if not hardy, Elizabeth walked from Truro to Plymouth with the idea that she would take up residence with her sibling. Unfortunate as usual, Elizabeth could not find her sister. Elizabeth, who in our day and age would be termed a little girl, was penniless, starving and alone. Like so many nameless others of her generation, she turned to the sea.

Dawning a boy's trousers (and perhaps looking similar to this drawing by Thomas Rowlandson), Elizabeth signed aboard HMS Hazard at Plymouth in the last half of 1806 using the name John Bowden. Deemed fit to serve, she was rated a boy 3rd class and given the usual advance on her pay. Hazard left for sea not long after the new boy was taken aboard. No one seems to have questioned her sex, at least not right away.

Within six weeks something occurred, history is silent as to what, that gave Elizabeth's gender away. One wonders if her menarche wasn't the culprit but that is purely speculation. At any rate, rather than being turned ashore at the next port, Captain Charles Dilkes gave Elizabeth a separate sleeping space and made her an assistant to the officers' stewards. This would have kept her out of the general ship's population and put her more closely in contact with not only the stewards but the galley crew as well.

With all this, Elizabeth would probably have fallen through the cracks of history as did so many other women at sea. But a well publicized case of sodomy aboard HMS Hazard, and Elizabeth's insistence that she had witnessed at least one of the incidents in question, brought her briefly into the lime light.

In August of 1807, while the ship was underway, Lieutenant William Berry was accused of regular abuse of a boy named Thomas Gibbs. Berry was twenty-two at the time but Gibbs, a ship's boy second class, had to have been younger than fourteen as he was not charged at the court-martial. According to the trial records, Gibbs finally got fed up with Berry's actions and told the gunroom steward, John Hoskins, what was going on. From the young man's testimony it sounds as if there was physical as well as sexual abuse going on, although Hazard's surgeon would say that he could "find no marks on the boy" and that Gibbs had only "complained of being sore".

Hoskins took Gibbs to Captain Dilkes and had him repeat his story. Berry was questioned by the Captain who was evidently inclined to believe the boy. The Lieutenant was arrested and a court-martial was arranged in October, aboard HMS Salvador del Mundo, when Hazard reached Plymouth once again.

I won't go into the details of the trial, which was presided over by Admiral John Duckworth, as that is not the focus of this post. What is interesting is that Elizabeth Bowden, known to be a girl, felt comfortable enough to step up and offer her story in the case. Even more fascinating is that the Royal Navy court took her testimony, it seems without batting an eye.

Elizabeth claimed to have seen an exchange between Berry and Gibbs by peering through the keyhole of Berry's cabin. She was asked if she observed Gibbs entering Berry's cabin frequently and answered yes. When asked "...and what induced you to look through the keyhole?" Elizabeth replied, quite simply, that Gibbs in Berry's cabin seemed curious, and "...I thought I would see what he was about." The court recorded this testimony and noted that she was "Elizabeth alias John Bowden (a girl) borne on the Hazard's books as a Boy of the 3rd class."

Lieutenant Berry, who called in family and friends to vouch for his good character and even had a girl come along side ship and offer to marry him, was found guilty under the 29th Article of War and hanged from the starboard fore yardarm of Hazard on October 19th.

And that is all we know about fourteen-year-old Elizabeth "John" Bowden. Whether she continued on in navy service, like the intrepid William Brown, found a husband and settled down, or came to what would then have been called a bad end is impossible to say. Her brief story, however, gives us another example of the much debated acceptance of women at sea.

Elizabeth had an older sister who, to the best of the girl's knowledge, lived in that haven of the Royal Navy: Plymouth. Being nothing if not hardy, Elizabeth walked from Truro to Plymouth with the idea that she would take up residence with her sibling. Unfortunate as usual, Elizabeth could not find her sister. Elizabeth, who in our day and age would be termed a little girl, was penniless, starving and alone. Like so many nameless others of her generation, she turned to the sea.

Dawning a boy's trousers (and perhaps looking similar to this drawing by Thomas Rowlandson), Elizabeth signed aboard HMS Hazard at Plymouth in the last half of 1806 using the name John Bowden. Deemed fit to serve, she was rated a boy 3rd class and given the usual advance on her pay. Hazard left for sea not long after the new boy was taken aboard. No one seems to have questioned her sex, at least not right away.

Within six weeks something occurred, history is silent as to what, that gave Elizabeth's gender away. One wonders if her menarche wasn't the culprit but that is purely speculation. At any rate, rather than being turned ashore at the next port, Captain Charles Dilkes gave Elizabeth a separate sleeping space and made her an assistant to the officers' stewards. This would have kept her out of the general ship's population and put her more closely in contact with not only the stewards but the galley crew as well.

With all this, Elizabeth would probably have fallen through the cracks of history as did so many other women at sea. But a well publicized case of sodomy aboard HMS Hazard, and Elizabeth's insistence that she had witnessed at least one of the incidents in question, brought her briefly into the lime light.

In August of 1807, while the ship was underway, Lieutenant William Berry was accused of regular abuse of a boy named Thomas Gibbs. Berry was twenty-two at the time but Gibbs, a ship's boy second class, had to have been younger than fourteen as he was not charged at the court-martial. According to the trial records, Gibbs finally got fed up with Berry's actions and told the gunroom steward, John Hoskins, what was going on. From the young man's testimony it sounds as if there was physical as well as sexual abuse going on, although Hazard's surgeon would say that he could "find no marks on the boy" and that Gibbs had only "complained of being sore".

Hoskins took Gibbs to Captain Dilkes and had him repeat his story. Berry was questioned by the Captain who was evidently inclined to believe the boy. The Lieutenant was arrested and a court-martial was arranged in October, aboard HMS Salvador del Mundo, when Hazard reached Plymouth once again.

I won't go into the details of the trial, which was presided over by Admiral John Duckworth, as that is not the focus of this post. What is interesting is that Elizabeth Bowden, known to be a girl, felt comfortable enough to step up and offer her story in the case. Even more fascinating is that the Royal Navy court took her testimony, it seems without batting an eye.

Elizabeth claimed to have seen an exchange between Berry and Gibbs by peering through the keyhole of Berry's cabin. She was asked if she observed Gibbs entering Berry's cabin frequently and answered yes. When asked "...and what induced you to look through the keyhole?" Elizabeth replied, quite simply, that Gibbs in Berry's cabin seemed curious, and "...I thought I would see what he was about." The court recorded this testimony and noted that she was "Elizabeth alias John Bowden (a girl) borne on the Hazard's books as a Boy of the 3rd class."

Lieutenant Berry, who called in family and friends to vouch for his good character and even had a girl come along side ship and offer to marry him, was found guilty under the 29th Article of War and hanged from the starboard fore yardarm of Hazard on October 19th.

And that is all we know about fourteen-year-old Elizabeth "John" Bowden. Whether she continued on in navy service, like the intrepid William Brown, found a husband and settled down, or came to what would then have been called a bad end is impossible to say. Her brief story, however, gives us another example of the much debated acceptance of women at sea.

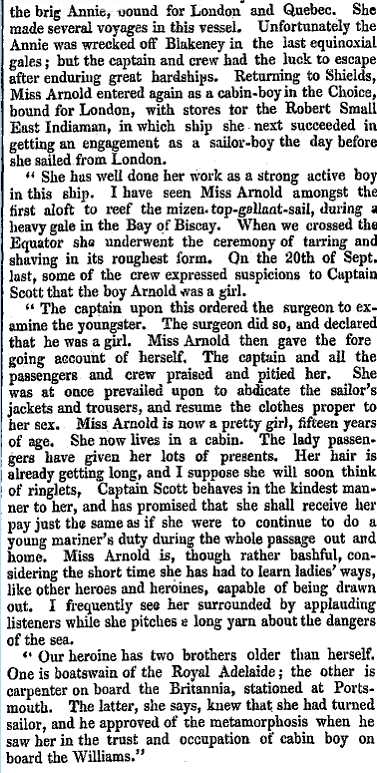

Women Who Have Become Sailors

Colonist, Volume XXVII, Issue 4355, 22 January 1886, Page 4

In the reign of George III. an Irishwoman named Hannah Whitney served for five years in the Royal British Navy, and kept her secret so well that she was not known to be a woman until she retired from the service.

A few years later, a young Yorkshire girl walked from Hull to London in search of her lover. She found him enlisted on His Majesty's man-of-war Oxford, and thereupon she donned a sailor's suit, assumed the name of Charley Waddell, and enlisted on the same ship. Her lover, not being as faithful to her as she to him, deserted the ship, and in attempting to follow his example she was arrested and her sex discovered. The officers raised a contribution for her, and she was dismissed from the service and sent home.

In 1802, a Mrs. Cola became somewhat famous by serving on board a man of war as a common sailor. She afterwards resumed her proper attire and opened a coffee house for sailors.

In 1800, a girl of 15 tried to ship at London on board a South Sea whaler, and being refused, she put on boy's clothes, hired herself to a waterman, and became very skilful in rowing. She did not learn to swim, however, and one day the boat capsizing, she was nearly drowned. In this crisis her sex was discovered, and she ceased to be "jolly young waterman," and became a dometic servant in her proper apparel.

Another girl, aged 14, named Elizabeth Bowden, being left an orphan, went up to London in 1807 from a village in Cornwall, in search of employment. She, did not succeed in finding such work as she desired, and putting on male attire, she walked to Falmouth, and enlisted as "boy" on board his Majesty's ship of war Hazand, and did good service aloft and beowv Her sex was finally discovered, however, and by the kindness of the officers the poor girl was placed in a proper position.

Still another, named Rebecca Ann Johnston, had a cruel father, who dressed her as a boy when she was 18 years of age and apprenticed her to a collier ship where she served for lour years.

In 1814, when the British war vessel Queen Charlotte was being paid off, a negro woman was found among the crew, who had served eleven years under the name of William Brown, and had become so expert a sailor that she was promoted to the captain of the foretop. She had all the peculiarities of a good sailor, and had kept her secret so well that none suspected her real sex.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)